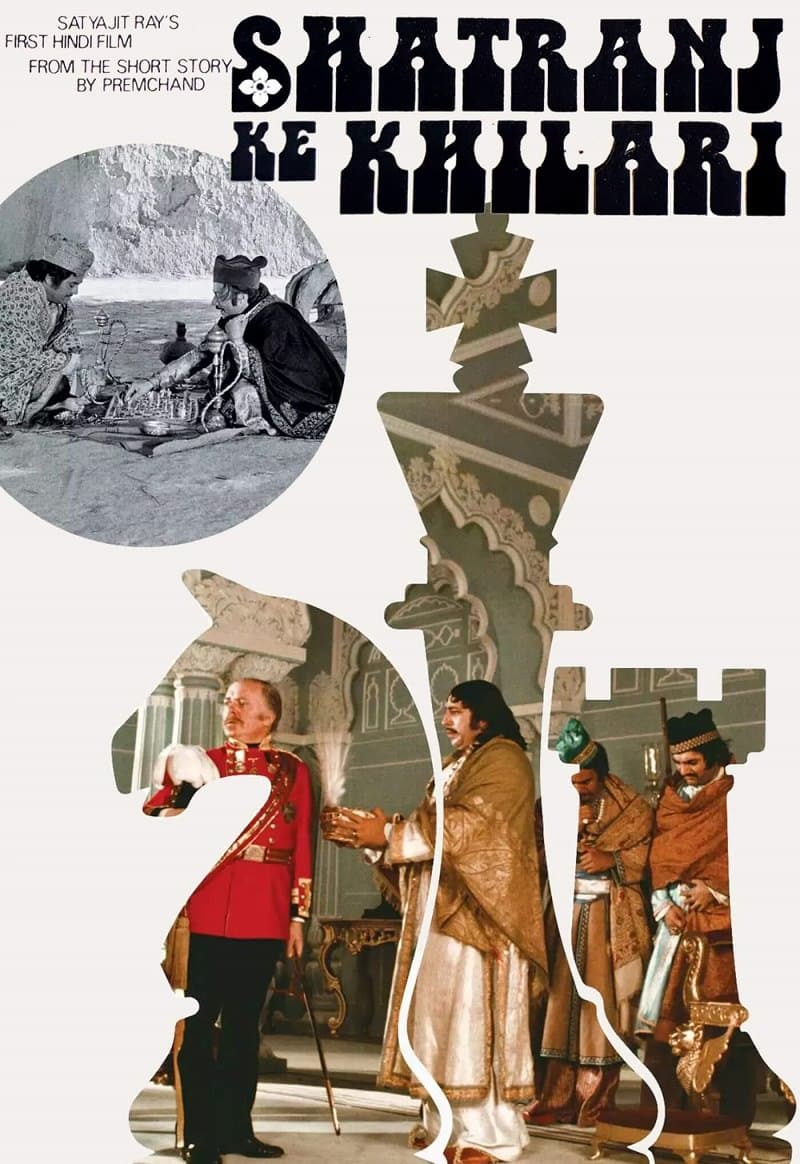

Shatranj Ke Khilari [Eng: The Chess Players] is a 1977 Hindi film written and directed by Satyajit Ray. Based on Munshi Premchand’s short story by the same name, the film is set in 1856 when the princely state of Oudh was annexed by the East India Company and the titular ruler of the state, Nawab Wajid Ali Shah was deposed.

Shatranj Ke Khilari was the first and only full-length Hindi feature film made by Ray. It had an ensemble star including Sanjeev Kumar, Amjad Khan, Richard Attenborough, Shabana Azmi, and Tom Alter. It achieved critical acclaim and was internationally released after being dubbed in English. The film was nominated for the 51st Academy Awards and was preserved by the Academy Film Archive in 2010.

Cast

- Amjad Khan – Wajid Ali Shah

- Sanjeev Kumar – Mirza Sajjad Ali

- Saeed Jaffrey – Mir Roshan Ali

- Shabana Azmi – Khurshid, Mirza’s wife

- Farida Jalal – Nafisa, Mir’s wife

- Sir Richard Attenborough – Gen James Outram

- Victor Banerjee – Madar-ud-Daula

- Veena – Queen, Wajid Ali Shah’s mother

- Farooq Sheikh – Aqueel

- Tom Alter – Capt Weston

- David Abraham – Munshi Nandlal

Crew

- Direction – Satyajit Ray

- Story – Munshi Premchand

- Screenplay – Satyajit Ray, Shama Zaidi, Javed Siddiqi

- Editing – Dulal Dutta

- Music – Satyajit Ray

- Cinematography – Soumendu Roy

- Choreography – Birju Maharaj

- Narration – Amitabh Bachchan

- Production – Suresh Jindal

Story

Shatranj Ke Khilari is set in the Lucknow of 1856. Wajid Ali Shah, the indifferent Nawab of Oudh, is soon going to be the last in his line. The British East India Company has spread its tentacles across much of India, either directly or through subsistence treaties which Rajas and Nawabs who have become titular rulers while the real reign is in the hands of the Company Bahadur.

The destiny of Lucknow now remains in the hands of Lord Dalhousie who is hell-bent to push the frontiers of the empire as much as he can. Using Doctrine of Lapse, he has already gobbled up the princely states of Punjab, Burma, Tanjore, Satara, and Jhansi and now has his eyes set on the largest and juiciest plums of all – Oudh.

Wajid Ali Shah is a gifted poet and musician, a multifaceted artist in his own right. What he is not, however, is a capable ruler. Seemingly resigned to his fate, he prefers the pleasures of his court and harem to any matters of statecraft. His able prime minister, Ali Naqi Khan, is a disappointed man, torn between his sorrow at witnessing the fall of once-great Oudh, and his loyalty to the Nawab.

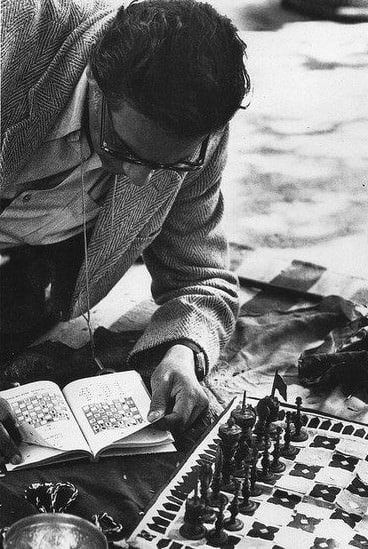

Mirza Sajjad Ali and Mir Roshan Ali are two jaagirdars and friends who live in Lucknow. They have become a mirror of Lucknow, part of a fading, decadent order that is crawling towards its doom with a remarkable lack of enthusiasm or concern. However, there is one thing that our protagonists are still passionate about – the game of chess. They play chess all day, the traditional style one, oblivious of the new style of chess played by the British, literally and figuratively.

Their wives feel understandably neglected. While Mirza’s wife Khurshid continues to resent her husband’s lack of attention towards anything other than chess; Mir’s wife, Nafeesa makes up for it by getting into a torrid affair with a young nephew. Mir is aware of the affair but has chosen to ignore it in favor of maintaining the status quo.

Meanwhile, the Nawab is facing a political checkmate. The Governor-General makes a pretext of misrule in Oudh and has sent General Outram, the British resident of Lucknow, to capture Lucknow. Though Wajid Ali Shah and his court know that this step by the British is an unjust and treacherous one, they neither have the will nor the means to put up a fight. Since Oudh had a treaty of friendship with the Company, it never felt the need to have a significant military. Now the tiny army of the kingdom is no match for the might or the craftiness of the enemy.

Mirza and Mir have already learned about the Company troops marching towards Lucknow. Fearing that they might be called to fight for the Nawab against the British, they retire to a remote village so that they can continue playing chess. Away from the din in Lucknow, they keep playing their little games on the board.

In Lucknow, the Nawab looks in the face an impending defeat and decided to abdicate the throne to avoid the bloodshed of his people, a thumri composed by him playing in the background.

Babul mora, naihar chhooto jaaye…

[O father, my home is being left behind…]

As the British troops march unopposed in Lucknow, our chess players have a fight over the game. After they have almost killed each other, a ashamed Mir says, “We cannot even cope with our wives, how can we face the company’s army?”

Commentary

Shatranj Ke Khilari was Satyajit Ray going way off his comfort zone. The film was in Hindi, a language he was not well versed with, had a star cast from Bombay, and was perhaps his most expensive film ever, even if it would be considered made on a shoestring budget going by the Bollywood films of the time.

The original story by Munshi Premchand was short, hardly 10 pages long, and focussed mostly on the chess-playing aristocrats. Ray extended the plot and developed the characters of both Wajid Ali Shah and his Wazir, and the British General Outram and his aide Capt Weston. The English dialogues were written by Ray himself; and even in their brevity, the spark is difficult to miss.

What makes Shatranj Ke Khilari a timeless classic is a nuanced and delicate treatment Ray has given to him, treading on the fine line dividing a historical drama and a political satire. It is worth noting that this film was made during one of the darkest phases of independent India, the Emergency imposed by Indira Gandhi. This was a time when the illusion of a new India had worn off and the crafty decadence of the political system had made itself evident in the rot of the country. While the premise of the film is set 120 years before the film was made, its characters cogs in the wheels of empires and kingdoms long gone, one cannot help but compare the events to the contemporary collective embarrassment that we call democracy. In a tragic yet funny way, it is difficult not to identify with the indolent protagonists.

Satyajit Ray might not have been the greatest master of period dramas, but the way he developed several storylines, developing them and bonding them together is nothing short of magical. He used the medium of a chess game not only to establish the central characters and the conflict between them, but he also smoothly transitioned from them to the historical and especially political context within which these characters existed. It is the touch of Ray that makes Shatranj Ke Khilari a non-linerar metaphor, and a masterfully created one at that.

Easy Targets Don’t Interest Me…

“Easy targets don’t interest me very much. the condemnation is there, ultimately, but the process of arriving at it is different. I was portraying two negative forces, feudalism, and colonialism. You had to condemn both Wajid and Dalhousie. This was the challenge.

I wanted to make this condemnation interesting by bringing in certain plus points of both sides… by investing their representatives with certain human traits.

These traits are not invented but backed by historical evidence.

I knew this might result in a certain ambivalence of attitude, but I didn’t see Shatranj as a story where one would openly take sides and take a stand.

I saw it more as a contemplative though the unsparing view of the clash of two cultures – one effete and ineffectual and the other vigorous and malignant.

I also took into account the many half-shaded that lie-in-between these two extremes of the spectrum…

You have to read this film between the lines.”

– Satyajit Ray, 1978

The Making of Shatranj Ke Khilari

[Excerpts from ‘The mother tongue & the other tongue’ – Shama Zaidi, 1978]

The Premise

When Satyajit Ray first thought of what his approach to the script would be, he seemed quite excited by the idea of being able to juxtapose the stasis of the chess-playing noblemen with the turmoil of the battle, which must have accompanied the annexation of Oudh.

This was, of course, before he had read anything about the actual events which occurred at the time of the annexation. Because when he did, he discovered that there was no battle at all – in fact not a single shot was fired and Wajid Ali Shah, the last King of Oudh gave up his throne without any recourse to his action.

At this point, he was almost on the point of abandoning the project altogether, as he thought the film would suffer from a lack of movement. But then he thought it over and decided to treat the story of the chess players in a tongue-in-cheek fashion, juxtaposing their little drama with the machinations of the East India Company and the bewildered outrage of Wajid Ali Shah.

As a child, Ray spent his vacations in Lucknow visiting his uncle and remembers being entranced with the old world courtliness of the typical Lucknowi. Remnants of the old feudal Lucknow in the form of speech, mores, and amusement continued to be found in Lucknow until 1947 when many of the jagirdars and nawabs of Lucknow decided to throw in their lot with Pakistan and migrated to that country.

Indolent, aristocratic Lucknow represented a world in itself. The Lucknowi nawab or nobleman has become a stock figure in the popular imagination – a quixotic combination of exaggerated good manners, courtliness, quaint eccentricities, and fin-de-siecle ennui.

When Ray had completed the first draft of the script with all the dialogues, he wanted all the portions in Urdu to be translated. But he said it was not to be a literal translation – the spirit was more important

After the dialogues had been rendered in Urdu, he went over them word by word asking for a change of word here, a dropping of a certain phrase there, the addition of a paragraph, or the quotation of a couplet.

Unlike his other films, Ray has made almost no use of non-actors except in the case of the little boy, Kallu, whom the chess players meet in the village. Probably because he was working in a new language and because it was a historical film, he preferred working with professionals, with whose work he was familiar. He says that in Bengali he is able to work with new actors because he can instruct them about each gesture and the exact intonation of each word by demonstrating what he wants – but not being as fluent in Hindi he could only do so by suggestion.

Casting

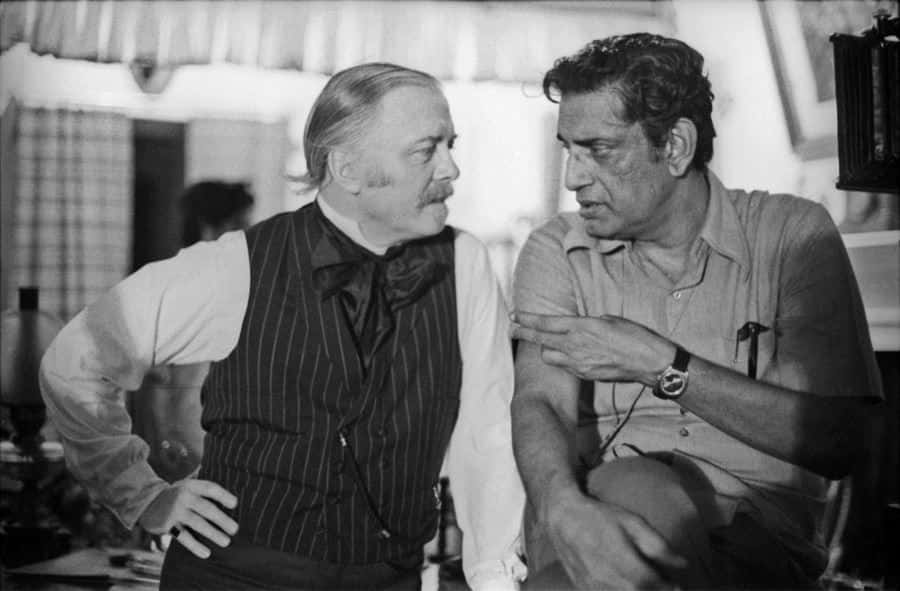

Amjad Khan, who played Wajid Ali Shah, was a popular ‘bad guy’ in Hindi films. When he looms large on the screen, the audience knows trouble is on the way. Rad had set his heart on having Amjad play the last King of Oudh, and when just a few weeks before the film was to start, Amjad was involved in a very bad car accident. Ray said he was prepared to delay the film rather than have anyone else play the role.

Just a short time before this, another actor, Sanjeev Kumar, one of the two chess-playing noblemen had a mild heart attack and was advised complete rest for some months. Sanjeev Kumar, whose mother tongue was Gujarati, had worked on the Hindi stage and screen for many years.

The project really seemed to be jinxed when it was heard that the second nobleman, Saeed Jaffrey, had also been involved in a car accident at about the same time as Amjad. Saeed lived in London and worked there in films, television, and theatre. This was his first appearance in any Indian film, Ray had met him in London many years ago and had seen him on stage. He met him again, in between connecting flights sometimes later, and Ray, half in jest, made him promise that if he ever made a film in Hindi and Urdu, Saeed was to be cast. When he received Ray’s letter offering him a role no one was more surprised than Saeed.

Ray and Attenborough had served on the jury of a film festival in Delhi and Ray thought he would like him to play Outram. As the film was not previously scheduled and this was not possible because Attenborough was busy filming A Bridge Too Far. After this, Ray considered many other actors. Then due to a delay in the film, it was possible for Attenborough to squeeze in enough time to make an appearance in Shatranj Ke Khilari.

Shabana Azmi, who plays Sanjeev Kumar’s neglected wife is an actress admired for her intense and memorable roles in many noteworthy films. Ray was initially skeptical about Shabana playing the role. In a letter to the producer Suresh Jindal he said, “I’m still not hundred percent happy about Shabana in the role of Mirza’s wife. She is too young and well-endowed not to be able to “rouse” Mirza in the crucial scene. Madhur (Jaffrey?) would certainly be more convincing here”.

Shabana on the other hand was spooked to be a part of this project, even if her role would be limited to just a few things. “Suresh, if Ray wants me to hold a jhadu for one-shot only, I will gladly do it. Work with Ray? Wow!”

As it turned out, the decision to cast her was a good one, and she held her own in the film with a powerful portrayal of Khurshid.

Farida Jalal, who plays Saeed Jaffrey’s young and wayward wife is a very versatile actress and especially good at slightly comic roles.

Recreating The Past

Recreating the period was as difficult for Ray as working in a new language.

He first thought that certain portions of the film could be shot on actual location and the rest on sets. A trip was made to Lucknow for this purpose and it was found that most of the palaces and buildings of the period had been destroyed during the 1857 uprising.

So, except for the last sequence which was shot in a village near Lucknow, almost everything else had to be constructed – largely from conjecture – by Ray’s designer Bansi Chandragupta.

Ray himself would draw the rough sketches for the sets that he wanted and Bansi would modify them accordingly. The patch-work chessboard, the crown, and the throne used by Wajid Ali Shah were designed by Ray himself. He also worked out the palette of colors to be used in the costumes and the décor of the whole film. He stuck cuttings of all the fabrics used in the film in his little red book.

Photo: Outram’s Study, a sketch by Satyajit Ray.

This red book was a stoutly bound volume of the sort traditionally used by merchants to keep their accounts. Ray likes them to use his personal copy of the script as they were sturdily bound and the paper is thick and glossy. In this red book, he writes all the dialogues – in this film he transliterated everything into Bengali letters – along with small sketches of the shot composition he wanted and everything he needed.

Ray would spare no pains to track down a particular prop required for a scene, whether it was a piece of Victorian bric-a-brac, a Siamese cat, or a silver hookah. The most elusive of these was the Siamese cat, which disappeared during the dance scene. It was later discovered on the roof of a studio, when it bit the assistant cameraman and ran away altogether, only to re-appear after the scene had been completed.

The borrowing of all the cashmere shawls, gold and silver hookahs, Victoriana, chandeliers lamps, and utensils was itself a ritual.

Ray himself visited the houses of collectors and old Calcutta families. They were only too pleased to lend their heirlooms to ‘Manik Babu’ as Ray is known in Calcutta. Many of them would later come to watch the shooting of the scenes where their loaned items were used. In each of these houses, we would be graciously offered tea and traditional Bengali snacks, and after a suitably polite interval the things which Ray wanted to borrow were displayed, some were selected and then packed to be carried to the studio. I think this sense of involvement on the part of everyone concerned us what gives Ray’s films their great feeling of warmth and humanity.

– Shama Zaidi (1978)

Awards & Recognition

- Berlin International Film Festival – Golden Bear (nomination) (1978)

- Filmfare Awards (Best Film, Best Director, Best Supporting Actor)

Trivia

- The choreography was composed by Birju Maharaj and is based on a composition by his grandfather Bindadin, who was the leading dancer in Wajid Ali Shah’s court.

- The thumri “Babul mora naihar chhuto jaaye..” is a composition by Wajid Ali Shah.

- There were two earlier and unreleased attempts to make a film on Wajid Ali Shah, an Ashok Kumar and Suraiya starrer in 1953, and another made by British Directory Herbert Marshall.

- Satyajit Ray made only 2 movies in Hindi, one was Shatranj Ke Khiladi and the other one is Sadgati, which was a short film.

Reference

- Wikipedia – The Chess Players (film)

- IMDB – The Chess Players (1977)

- DFF Archives – Indian Panorama

- DFF Archives – National Film Awards

- The Mother Tongue & The Other Tongue – Shama Zaidi

- Satyajit Ray Official Website – Shatranj Ke Khilari (The Chess Players)

- The Book Review Literary Trust – The High-Priest of Indian Cinema

- The Print – Ray’s ‘Shatranj Ke Khilari’ asked difficult political questions & is an election must-watch

- Rediff – Excerpts from Manik And I, My Life with Satyajit Ray, by Bijoya Ray

- Disney Hotstar – Watch Shatranj ke Khilari