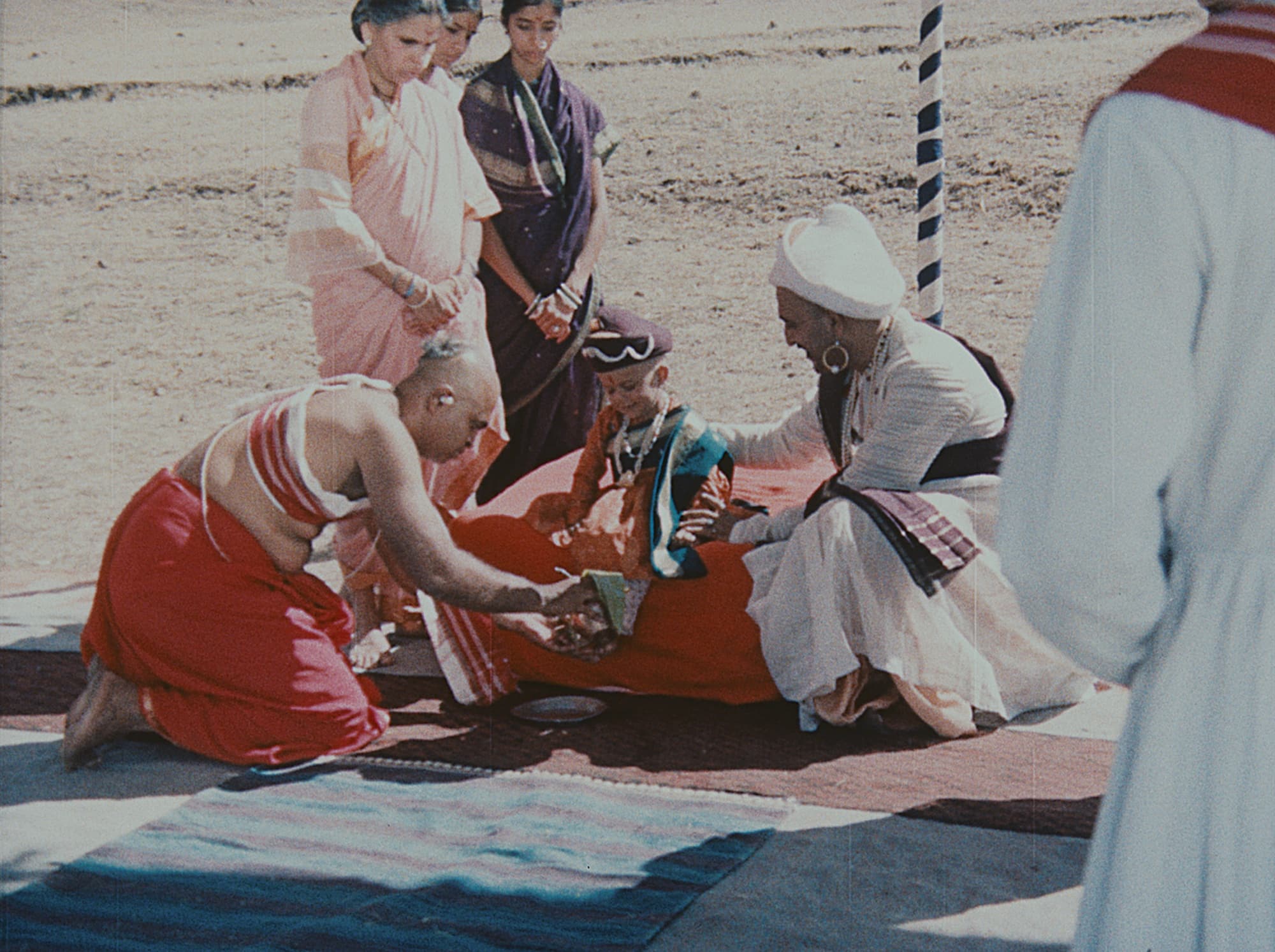

Ghasiram Kotwal is a 1976 Marathi Film based on a play of the same name by Vijay Tendulkar. The film was the first venture of YUKT Film Cooperative, an experiment in collective filmmaking, and was made by a group of filmmakers – K. Hariharan, Kamal Swaroop, Mani Kaul, and Saeed Akhtar Mirza. It had Mohan Agashe, Om Puri, and Rajni Chauhan in prominent roles.

Ghasiram Kotwal is based on the lives of Nana Phadnavis, an influential minister of the Peshwa in the late 18th Century; and Ghasiram, his law and espionage enforcer in Pune. A deeply political film, Gashiram Kotwal is a fascinating tale of lust and bloodlust, political intrigues and treachery, shifting loyalties and murderous despotism while the British nibbled into the Maratha empire.

Crew

- Om Puri – Ghasiram

- Mohan Agashe – Nana Phadnavis

- Rajni Chauhan – Ghasiram’s wife

Crew

- Direction – K. Hariharan, Kamal Swaroop, Mani Kaul, and Saeed Akhtar Mirza

- Screenplay – Vijay Tendulkar

- Cinematography – Rajesh Joshi, Binod Pradhan, Manmohan Singh

- Music – Bhaskar Chandavarkar

Story

Ghasiram Kotwal is set in the period from 1773 to 1797 AD, the fag end of the Peshwa hegemony in the Maratha Confederacy. Peshwa Madhav Rao II, born in 1774, is the Peshwa however, the real power is wielded by Nana Phadnavis, his prime minister. Nana is a shrewd politician embroiled in a constant tussle with other power centers among the Marathas. Raghunath Rao, the young Peshwa’s granduncle has already allied with the British who are eyeing the empire with keen interest.

As Nana is busy strengthening his hold on the young Peshwa, Ghasiram Savaldas, a brahmin from Kannauj arrives upon the scene. He is installed as Nana’s espionage agent in Poona.

Ghasiram becomes increasingly formidable in the corridors of powers after giving away his daughter to Nana in marriage, his sixth wife. He becomes a mirror image of Nana, a tyrant unleashing a reign of terror against those who are perceived to be plotting against the government. His swift rise earns him both friends and enemies, the latter more than the former. However, he continues his relentless pursuit of those who he perceives as the enemy of the state.

In the heart of a feudal and decadent Peshwa capital, sprouts intrigue, murder, alliances and he increased interferences of an alien power – the East India Company. Through his espionage network, Nana gets a whiff of the subversive operations of the British. He manages to route them at the Battle of Wadgaon (1779) which keeps the company at bay for a while.

The turn of events takes a dark turn when a group of Brahmins from Andhra suffocates to death in a dungeon where they were thrown on Ghasiram’s orders. The brahmin class in Poona still exercises significant clout and they are understandably angered. Things come to a boiling point and an enraged mob, unable to have Nana’s, demands Ghasiram’s head instead. He is arersted and pushed into a prison cell where he awaits the decision on his fate.

Nana visits Ghasiram in the jail and tries to placate him by offering spiritual solutions to life and death. Ghasiram, on the other hand, has realized the treachery done with him, but all protest has died in him by this time.

Ghasiram Kotwal is executed by the public. Nana Phadnavis escapes unscathed. The Peshwas hang on for some more time, while most other Indian states have been gobbled up by the Company, only to fade away soon.

Commentary

Ghasiram Kotwal was the first venture of YUKT, an experimental film cooperative that comprised sixteen students from Pune’s Film and Television Institute (FTII). The play written by Vijay Tendulkar, and directed for the stage by Dr. Jabbar Patel, became their maiden effort as this was a topic already familiar to the public. Tendulkar was also the script writer for the film and this helped bring a tighter coherence between the original play and the film.

However, the film needed to be more than just a cinematic remake of the play. While the play had concentrated on the decadence of the brahmins of Poona, with the spectators taking an almost voyeuristic delight in Nana’s dalliances with young females; the canvas of the film was broader and took a darker political turn.

The film quotes extensively from Nana’s autobiography; the excerpts heard over images from the life and indulgences of the period. It strongly suggests that debauchery cannot sustain without the crutches of orthodoxy.

“We set down the structure on a sixty-foot scroll illustrating the film’s movement. The dialogue was to match this sequence. The film follows no linear plot, individual historical events are linked (or rather separated) by title cards which carry the events forward”

– Vijay Tendulkar

Power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely. Ghasiram Kotwal was made during the same period that saw the unraveling of the Emergency and the darkness that it brought with it.

“The parallels with Indira Gandhi’s tyrannical rule were striking; a hegemonic impulse articulated by the use of the police as a means of manifest repression found a metonymic parallel in the way Nana used Ghashiram to enforce terror amongst the Brahmins. Such timely and considered ideological engagement avoids polemicizing, instead of relying on a self-reflexive approach, combining some of the dance traditions of Indian culture with Brechtian devices (the omniscient narrator, title cards, direct camera address to name a few) to fuse together a postcolonial non-linear dialogue of history and politics that is both diachronic and synchronic.“

[Excerpts from Ghasiram Kotwal – Omar Ahmed]

The characters in the film emerge not as characters in their own right, but as symptomatic of the period’s malaise. Ghasiram is an outsider, climbing to power through Nana. To Nana, on the other hand, an outsider is the perfect agent, and the perfect scapegoat when the time comes.

Mani Kaul was the senior-most director associated with this film and his touch is evident in many scenes such as the one where Nana and Ghasiram meet for the first time, emerging as mirror-images and walking towards each other, morphing into one till Nana engulfs his servant completely in a ‘spatial eclipse’, as if he swallows him up.

This symbolism is typical of the film’s style for the rise and fall of Ghasiram is an inquiry into the causes of the decline of the Maratha empire. The brutal confinement of the brahmins to a dungeon where they suffocate to death is the culmination of a chain of unbridled actions that serve to bring the downfall. Only in the final confrontation with his master does the condemned Ghasiram come alive, when he listens with blazing eyes to his former master as he elocutes on the illusionary nature of life.

“Ghashiram, the policeman, is the alter ego of the ruling body. We become spokespersons for our masters and mirror our masters more sincerely than the masters themselves. The story goes that when a few Andhra Brahmans had come to Pune, Ghashiram put them behind bars. They suffocated and died. This created a huge uproar. People demanded that Ghashiram be sentenced. Nana Fadnavis obliged. The system sacrifices pawns because people believe that the pawn is the problem.”

– K Hariharan

The contemporary critical reaction to Ghasiram Kotwal was muted and it disappeared from theatres in Pune within a week of the release. The film was screened later in a film festival in Chennai (then Madras) and subsequently selected for a screening at the 1978 Film Festival. While the original film was destroyed, a copy of it sent to Germany was restored by Berlin-based Arsenal Institute, one of the only two Indian films to be restored by the institute.

There has been a renewed critical interest in the film, with some reviewers considering it a seminal work in Indian avant-garde cinema, in terms of ideological and aesthetics experimentation.

Reference

- Wikipedia – Ghasiram Kotwal (film)

- Filmgalerie 451 – Ghasiram Kotwal

- Movie Mahal – Experiments in Time & Space

- DFI Archives – Indian Panorama

- The Hindu – History reloaded